Crossing the Mersey: Tunnels, subways & bridges

by Kay Parrott

Liverpool is situated on the eastern bank of the River Mersey as it flows into Liverpool Bay and is separated at its narrowest

point from the Cheshire shore by just one kilometre. To the south the river widens which has the effect of concentrating the

tidal flow at Liverpool. Crossing the River Mersey has always presented a challenge; "the Mersey estuary is at once the heart of

Merseyside and its most divisive element". By 1330 the monks of the Benedictine Priory in Birkenhead had been granted the right to

operate a ferry across the Mersey. As Liverpool and Birkenhead grew there was an increasing need to move both people and

goods between the Lancashire and Cheshire sides of the river. The lowest bridging point at Warrington was 23 miles upstream,

although the river could be forded at Hale, but only at low water and not without danger. The first steam ferries went into

service around 1815 and until the 1930s ferries remained the most important way of crossing the river. In 1934 the Seacombe and

Birkenhead ferries were each still carrying 21 million passengers a year. Luggage boats continued to carry both vehicles and

luggage until the 1940s.

Liverpool is situated on the eastern bank of the River Mersey as it flows into Liverpool Bay and is separated at its narrowest

point from the Cheshire shore by just one kilometre. To the south the river widens which has the effect of concentrating the

tidal flow at Liverpool. Crossing the River Mersey has always presented a challenge; "the Mersey estuary is at once the heart of

Merseyside and its most divisive element". By 1330 the monks of the Benedictine Priory in Birkenhead had been granted the right to

operate a ferry across the Mersey. As Liverpool and Birkenhead grew there was an increasing need to move both people and

goods between the Lancashire and Cheshire sides of the river. The lowest bridging point at Warrington was 23 miles upstream,

although the river could be forded at Hale, but only at low water and not without danger. The first steam ferries went into

service around 1815 and until the 1930s ferries remained the most important way of crossing the river. In 1934 the Seacombe and

Birkenhead ferries were each still carrying 21 million passengers a year. Luggage boats continued to carry both vehicles and

luggage until the 1940s.

The Liverpool Guide of 1801, one of the earliest guide books to the town, noted that a bridge would be 'inadmissible

near the town as it would be greatly injurious to the navigation of the river' and 'a road tunnel under the river had never been

considered otherwise than as a fanciful project'. With advances in engineering technology there are now three tunnels under the

River Mersey, but no one has yet succeeded in building a bridge across the river. From the early nineteenth century there have

been numerous proposals, some more realistic than others, to either tunnel under the river or build a bridge over it, either road

or railway, using a variety of different routes. The first permanent crossing across the River Mersey was not established until 1886

when the Mersey Railway opened between James

Street, on the Liverpool side, and Green Lane, adjacent to the Camell Laird shipyards on the Wirral side, via Hamilton Square and

Birkenhead Central. The building of a passenger railway solved the problem of moving people from one side of the river to the

other, but the need to get vehicular traffic, both goods carts and private carriages remained.

The Liverpool and Birkenhead Subway

The Liverpool and Birkenhead Subway

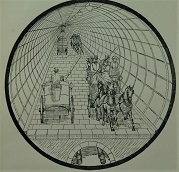

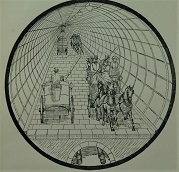

One tunnel scheme in the 1880s which progressed slightly further than others was a proposal to build a so-called 'subway'

between Liverpool and Birkenhead. The Liverpool and Birkenhead Subway Company held regular meetings and investors subscribed

money to the new company. The tunnel, for road traffic, was to be two miles long, starting to the rear of the Pier Head and

finishing in Hamilton Square, Birkenhead. The tunnel, with a diameter of 24.5 feet, allowed two lorries laden with cotton, to pass each other

in opposite directions and access would be via hydraulic lifts. Even before work had started it had been decided that the tolls

for using the subway would be less than the ferries, 9d for a one horse carriage as opposed to 1s on the ferry and just 1s for a

two horse omnibus, rather than 3s by ferry. In other words this would be cheaper, quicker and have the added advantage of not

being affected by weather or tides. However in 1892 the main contractor Henry Farnsby Mills went bankrupt: the Liverpool and

Birkenhead Subway Company was finally wound up in March 1896, with the original investors losing their money.

Webster and Wood's high-level bridge

Webster and Wood's high-level bridge

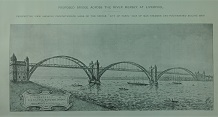

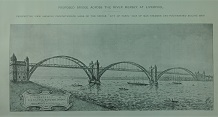

Detailed plans for a high-level bridge across the Mersey were put forward by John J Webster and John Thomas Wood in 1893.

Illustrations for their proposal show an arched suspension bridge, crossing in three spans, 150 feet above the highest spring

tides in the centre of the river, thereby accommodating the sailing ships, which still used the river even at the end of the

19th century. The roadway would be 40 feet wide, allowing two lines of wheeled traffic in each direction, plus outer footways for

pedestrians. This compared with a width of just 24.5 feet in the proposed Subway and would allow faster traffic space to overtake,

reducing potential delays. In addition there was to be an overhead electric tramway supported on columns in the centre of the

roadway and which could potentially be linked to the Liverpool Overhead Railway, opened the same year. To allay fears of problems in high

winds the tramcars and rails were designed 'so that they could not possibly be overturned in the strongest gale'. As yet another

added extra, one of the piers was designed as a landing place for transatlantic liners, with hydraulic lifts taking passengers up

to the roadway level. The cost was estimated at £1,730,000, excluding the cost of the tramway, and annual income from tolls was

estimated at £190,000, giving investors a potential return of 10 per cent. The designers stressed the advantages of a bridge across the

river, which would be safe, convenient and quick, and could be used in all weathers, day and night, including in foggy conditions,

with the additional bonus of a magnificent view from the bridge. Objections included the possible obstruction of the river by

the piers supporting the bridge and their effect on the tidal flow.

Helical roadways

Helical roadways

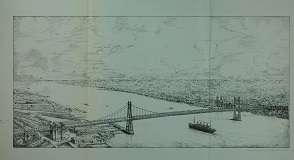

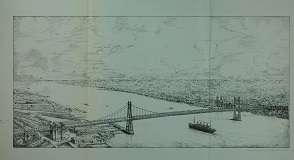

One of the major problems in constructing a bridge across the River Mersey was the need to provide adequate clearance for

shipping using the river, as indicated in Webster and Woods' design. The banks on both the Liverpool and Birkenhead sides are

relatively low lying and to achieve sufficient height, lengthy approach roads would be required to give an incline which could be

negotiated by horse-drawn traffic. It was estimated that a walking horse would take an hour to cross such a bridge, potentially

setting the very slow pace for all other traffic.

Even restricting traffic on a bridge to newly emerging motor vehicles and trams, capable of climbing steeper gradients, the

approach road on such a structure would be three quarters of a mile from the river, requiring a huge potential purchase of property

in the city centre. In 1912 Lloyd Heber Chase proposed a bridge with a novel approach. His solution was to build a

new type of approach, resembling a giant helter-skelter, with a helical roadway taking traffic up to the bridge and to be used by

both trams and motor traffic, with room for overtaking. The gradient could easily be increased or decreased by altering the

diameter. The space inside the building was not to be wasted as Chase suggested that it could be used as offices, accessed via

a central well. The span of the suspension bridge that Chase proposed would have been the longest in the world at 2,700 feet,

stretching from Liverpool to Seacombe, without a pier in the centre of the river, which he thought would be hazard to shipping.

He estimated the total cost of all this at £825,000.

1923 proposals

1923 proposals

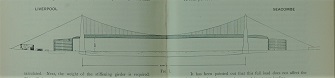

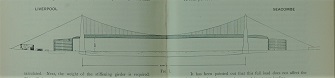

A Cross River Traffic Committee set up in 1921 looked at the merits of building either a bridge or tunnel across the River Mersey. The need

for another crossing had become increasingly pressing as cross river traffic had doubled between 1901 and 1921. Their report,

published in 1923, concluded that the narrowest part of the river between Seacombe and Woodside and the river wall in Liverpool

would be the most suitable crossing point. They suggested that by placing piers in the river a suspension bridge 2,200 feet long could be built. The proposed route ran

from the Victoria Monument at the top of Lord Street, finishing in Chester Street, Birkenhead. Because of the continuing need to

provide access to shipping the roadway would be a projected 200 feet above high water. The width of 90 feet would allow for a

"first class carriageway", with a footpath and two lines of tramways. The Committee then considered the issues surrounding the building of a tunnel. It was felt that any tunnel would need an internal

diameter of 44 feet. As in the 1880s Liverpool Subway scheme the use of lifts was considered, however it was decided that this

was not a practical option.

Similar arguments both for and against a bridge or tunnel were put forward as in previous schemes, such as navigation

problems, the length of approach roads and 'windy and inclement weather', but one issue not considered by earlier planners was

the risk of damage to a bridge from aircraft during war. A bridge would require more maintenance with continuous painting on a

structure, parts of which would be 450 feet above the river. A tunnel, on the other hand, would require continuous lighting and

ventilation, as well as pumping to remove water. However the relative total costs differed substantially, those for a bridge

estimated at £10,550,000 as opposed to £6,400,000 for a tunnel. At the beginning of their enquiry the working party had

expected to endorse the construction of a bridge, but their unanimous conclusion was in favour of building a tunnel and the

relative costs were undoubtedly persuasive. The first Mersey road tunnel, officially called the Queensway Tunnel, incorporated a

number of the proposals made in the 1923 report and opened in 1934, more than 130 years after building a tunnel under the River

Mersey was first suggested.

1960s proposals

1960s proposals

The opening of the Queensway Tunnel obviously relieved much cross-river traffic congestion, but by the 1960s, vehicular

traffic had increased way beyond what could have been anticipated in the 1920s and 30s. A report in 1960 by consulting engineers

Mott, Hay and Anderson considered no fewer than eight different options, six tunnels and two bridges, for crossing the Mersey,

with the consultants appearing to cover all eventualities. Proposals to build twin two-lane tunnels between either King Edward

Street, Marybone or South Castle Street and a site near to Seacombe Station were considered. Another idea, to connect the two dock

branches of the existing road tunnel to form a single two lane tunnel, was widely ridiculed in the local press, which referred to

it as the 'Mersey Mousehole' and at just 19 feet wide it would certainly have been very claustrophobic. The consultants

alternatively suggested that twin tunnels could be built to the south of the Queensway Tunnel.

In common with the 1923 report ideas for a bridge across the Mersey were also considered, either from Upper Parliament Street

to Victoria Park, Higher Tranmere or from the Dingle to Birkenhead/Rock Ferry. The problems of height above the river and the

gradient of approach roads were to be mitigated by making use of higher ground to the south of Liverpool's centre and at Tranmere,

with much use made of elevated roads and roundabouts, either linking the bridge with the New Chester Road and Woodchurch Road or

Mount Road, Higher Bebington. Estimates for the various options ranged from £8.9 million to £27 million. The consultants actually

recommended a bridge from Parliament Street to Victoria Park emphasising that the best place for a new river crossing would be to

the south of the Queensway Tunnel. Despite their recommendations the next river crossing was a tunnel not a bridge, built to the

north of the existing Mersey tunnel.

The 1960s saw suggestions for a number of River Mersey crossings in local newspapers, one of which was for a direct road from

the East Lancashire Road in Liverpool, across the Wirral peninsular to the Point of Ayr in North Wales. It was to be elevated along its

entire length, giving 'a revolutionary answer to all traffic troubles', but undoubtedly ruining the area in the process. Land

reclaimed in the River Dee and around Hilbre Island would become an inland hill. Other ideas included a monorail connecting the

new estates of Speke and Huyton, with New Brighton, West Kirby and Rock Ferry, and a crossing of the Mersey between Garston and

Eastham, with docks, warehouses, industry and housing built on land reclaimed across the entire width of the river. An under

river shuttle service, making use of space beneath the roadway of the Queensway Tunnel was also proposed, with a continuous

system of carriages, linked by moving platforms and escalators, to multi-storey car parks, which would also include supermarkets,

near Hamilton Square, Birkenhead.

These are just some of the many ideas put forward over the centuries for crossing over the River Mersey. Some suggestions

were simply speculative, with little more than novelty value, some were technologically ahead of their time, and others were

serious, considered proposals, backed by detailed maps and analysis. As early as 1880 Alfred Holt predicted that 'except to

amuse sightseers traffic on the central ferries will cease' and this is the case today. After much prevarication a second Mersey

crossing, the Kingsway Tunnel, was completed in 1971 but it is interesting to speculate how different Liverpool would look today

with a high-level bridge across the Mersey in the centre of the city. In October 2017, the Mersey Gateway, a new bridge across

the River Mersey opened, but this 6-lane toll bridge crosses the river between Runcorn and Widnes, not Liverpool and Birkenhead.

Sheet numbers: Cheshire 13.03 Birkenhead; Cheshire 13.04 Birkenhead and Tranmere Waterfront; Lancashire 106.14 Central Liverpool

Kay Parrott, May 2020

Kay Parrott was formerly local history librarian at Liverpool Central Library. She has been writing for The Godfrey Edition

since 1989, and has written the introductions to 55 maps, principally for Merseyside but with occasional forays into north Wales.

Her most recent contributions were for Birkdale 1892, Southport 1892

and Bootle 1890. She is currently working on the introduction to a new 1st edition map for Anfield.

Most maps in the Godfrey Edition are taken from the 25 inch to the mile map and reduced to about 15 inches to the mile.

For a full list of maps for England, return to the England page.

Alan Godfrey Maps, Prospect Business Park, Leadgate, Consett, Co Durham, DH8 7PW / sales@alangodfreymaps.co.uk / 23 April 2020

Liverpool is situated on the eastern bank of the River Mersey as it flows into Liverpool Bay and is separated at its narrowest

point from the Cheshire shore by just one kilometre. To the south the river widens which has the effect of concentrating the

tidal flow at Liverpool. Crossing the River Mersey has always presented a challenge; "the Mersey estuary is at once the heart of

Merseyside and its most divisive element". By 1330 the monks of the Benedictine Priory in Birkenhead had been granted the right to

operate a ferry across the Mersey. As Liverpool and Birkenhead grew there was an increasing need to move both people and

goods between the Lancashire and Cheshire sides of the river. The lowest bridging point at Warrington was 23 miles upstream,

although the river could be forded at Hale, but only at low water and not without danger. The first steam ferries went into

service around 1815 and until the 1930s ferries remained the most important way of crossing the river. In 1934 the Seacombe and

Birkenhead ferries were each still carrying 21 million passengers a year. Luggage boats continued to carry both vehicles and

luggage until the 1940s.

Liverpool is situated on the eastern bank of the River Mersey as it flows into Liverpool Bay and is separated at its narrowest

point from the Cheshire shore by just one kilometre. To the south the river widens which has the effect of concentrating the

tidal flow at Liverpool. Crossing the River Mersey has always presented a challenge; "the Mersey estuary is at once the heart of

Merseyside and its most divisive element". By 1330 the monks of the Benedictine Priory in Birkenhead had been granted the right to

operate a ferry across the Mersey. As Liverpool and Birkenhead grew there was an increasing need to move both people and

goods between the Lancashire and Cheshire sides of the river. The lowest bridging point at Warrington was 23 miles upstream,

although the river could be forded at Hale, but only at low water and not without danger. The first steam ferries went into

service around 1815 and until the 1930s ferries remained the most important way of crossing the river. In 1934 the Seacombe and

Birkenhead ferries were each still carrying 21 million passengers a year. Luggage boats continued to carry both vehicles and

luggage until the 1940s.