In the foyer of Rochdale's Touchstones Heritage Centre is a 3-dimensional panorama, graphically showing the town set amongst the Pennine foothills. Its name, literally the 'dale of the Roch', is a clear hint as to its location, with streets climbing upwards, steadily rather than steeply, on either side. Today's modern trams have to drop cautiously down the Drake Street slope before swinging east into their Smith Street terminus, but a clearer view of the terrain is found in the steps that lead down from St Chad'ss church to the Town Hall, or the still cobbled Church Lane. Spot heights and benchmarks here show the descent from 475 ft close to the station to 391 ft by The Butts, and then up again to over 500 ft by the time we have reached the top of the map. Sadly the River Roch, which is here shown winding its way through the centre of town, has today been culverted away, out of sight and out of mind.

In the foyer of Rochdale's Touchstones Heritage Centre is a 3-dimensional panorama, graphically showing the town set amongst the Pennine foothills. Its name, literally the 'dale of the Roch', is a clear hint as to its location, with streets climbing upwards, steadily rather than steeply, on either side. Today's modern trams have to drop cautiously down the Drake Street slope before swinging east into their Smith Street terminus, but a clearer view of the terrain is found in the steps that lead down from St Chad'ss church to the Town Hall, or the still cobbled Church Lane. Spot heights and benchmarks here show the descent from 475 ft close to the station to 391 ft by The Butts, and then up again to over 500 ft by the time we have reached the top of the map. Sadly the River Roch, which is here shown winding its way through the centre of town, has today been culverted away, out of sight and out of mind.

Rochdale stood near the foot of a vast parish which stretched as far as Littleborough and Todmorden, and which was divided originally into four townships, Castleton, Spotland, Butterworth and Hundersfield. The last named was later split into several townships, including that of Wardleworth, which covered much of the future town centre and largely comprised the Buckley estate, owned by the family of that name until 1786 when it was sold to Robert Entwisle of Foxholes.

The Butterworth township was also divided into several important estates or hamlets, including Belfield, owned by a branch of the Butterworth family from the 16th century and taking its name from the River Beal. It was sold in the early 18th century to Richard Townley, a local mercer and steward to the estate, and remained with that family until 1851 when it was sold to Robert Nuttall. Belfield Hall was a substantial 17th century house set around a courtyard, with the frontage rebuilt in brick by Richard Townley in 1752. In 1911 the hall was described by the Victoria County History as "now nearly wholly dismantled, and is fast falling into decay. Two portions of the building - at the north-east corner, and on the west side of the quadrangle - are occupied as cottages, and these are the only parts of the old house at present in a state of repair. The rest of the house, including the 18th century south wing, is little better than a ruin. The doors are open for anyone to enter, the windows are smashed, the floors broken, and the roofs do not keep out the rain. Less than twenty years ago the house presented an ordered appearance, which is now difficult to recall". The house, once a major landmark, has been lost, and the still surviving footbridge across the railway leads to an industrial estate.

Newbold was another hamlet within Butterworth township but Newbold Hall itself was so diminished that it doesn't even deserve mention on the map. It stood SW of Belfield Hall - their estates were separated by the Stanney Brook - on the W side of Newbold Street (immediately S of the 'D' of NEWBOLD). It originally comprised three buildings around a courtyard, though the south building was almost detached. It was described by the VCH as fronting onto a narrow street "in the midst of mean surroundings". The description continues: "The building appears to date from the 16th century, with later work in parts, and the north wing, which was until recently used as a public-house, has been almost entirely modernized and rebuilt. The central and south wings of the original building remain, but are in sadly dilapidated condition. The house has been divided into tenements, but only two portions are at present (1908) occupied, and the rest of the building is rapidly going to decay. The house is a good example of the smaller stone-built halls of this part of the country". A drawing of c.1840 shows a still handsome house. It has since been demolished, and an archaeological dig found little of great interest, but Newbold Street, rendered a cul-de-sac by a low bridge beneath the railway, is a pleasant, quiet street. By the late-19th century Newbold was growing into a substantial suburb of Rochdale and a church, St Peter\rquote s, was built in 1869, following the centre of the hamlet south-westward. St Peter'ss was designed by J Medland and Henry Taylor, and its exuberant (perhaps over-exuberant) colouring, red brick jostling with yellow stone, deserves our detour.

The original parish church of Rochdale, St Chad's, inevitably takes pride of ecclesiastical place, a medieval church with 13th, 14th and 15th century work but enlarged, restored and heightened in the Victorian period. The porch - handsome if today marred by a badly sited lamp-post - and top deck of the tower were by W H Crossland in 1873, a side-line while he was working on the Town Hall, and the chancel was extended by J S Crowther a few years later. The church is noted for its interior fittings, "a rich repository of carved woodwork, with much to enjoy and much to puzzle" according to Pevsner; there are mock-medieval monuments, apparently to bolster the genealogical pride of the Dearden family, lords of the manor, as well as work by the Saddleworth architect, George Shaw, and Burne Jones stained glass. West of the church the vicarage dated from c.1724, albeit enlarged a century later, and was built for the Rev Samuel Dunster who "adopted the plan of his house in Marlborough Street, London". Elsewhere in the town St James, simply marked 'Church' on the N side of Yorkshire Street, is a somewhat austere Commissioners' church of 1821; while St Mary le Baum, just north of the New Market, built in 1740 as a church for Wardleworth, was largely rebuilt, magnificently so, by Ninian Comper in 1909.

The vast Rochdale parish was clearly unmanageable and would eventually be further divided, with portions becoming part of Yorkshire. This unwieldy size may explain the modest commercial growth of Rochdale as a town in the medieval period; it gained a charter for a market in 1251 and was probably given borough status, but this quickly appears to have fallen into decline. In the event it was governed through a manorial court until 1825, then by commissioners - the town being defined as within a 3/4 mile radius of the old market place at the foot of Yorkshire Street - and was granted its municipal charter in 1856. In 1888 it became a county borough.

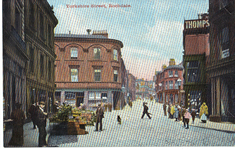

Despite this absence of municipal dignity, it was a busy and quite prosperous place, described by Celia Fiennes c.1700 as "a pretty neat town, built all of stone" and by Defoe, a few years later, as "a good market town, and of late much improved in the woollen manufacture". Wool would remain important well into the 19th century, and the weekly wool market - and Monday market for flannel, a particular Rochdale speciality - drew dealers and farmers from the villages about, quenching their thirst in the host of inns down Blackwater Street and Lord Street: The Half Moon, The King's Head, Duke of Wellington, Bishop Blaize, The Red Lion, The Clock Face and many more. Especially notable was the Butts Factory and adjacent mills on Smith Street, the principal works of Kelsall & Kemp, a manufacturer founded by Henry Kelsall (1793-1869), with a first mill built in 1835. The firm became especially famous for its 'Doctor Flannel'. Industrial dynasties are often worth following: Henry's daughter, Sarah Ainsworth Kelsall, married Sir Morton Peto, one of the great railway developers of the mid-19th century, who became an MP but whose reputation was ruined through bankruptcy.

Despite this absence of municipal dignity, it was a busy and quite prosperous place, described by Celia Fiennes c.1700 as "a pretty neat town, built all of stone" and by Defoe, a few years later, as "a good market town, and of late much improved in the woollen manufacture". Wool would remain important well into the 19th century, and the weekly wool market - and Monday market for flannel, a particular Rochdale speciality - drew dealers and farmers from the villages about, quenching their thirst in the host of inns down Blackwater Street and Lord Street: The Half Moon, The King's Head, Duke of Wellington, Bishop Blaize, The Red Lion, The Clock Face and many more. Especially notable was the Butts Factory and adjacent mills on Smith Street, the principal works of Kelsall & Kemp, a manufacturer founded by Henry Kelsall (1793-1869), with a first mill built in 1835. The firm became especially famous for its 'Doctor Flannel'. Industrial dynasties are often worth following: Henry's daughter, Sarah Ainsworth Kelsall, married Sir Morton Peto, one of the great railway developers of the mid-19th century, who became an MP but whose reputation was ruined through bankruptcy.

The first cotton mill was built in 1791 on Hanging Road, but it was only in the mid-19th century that this became the dominant industry. This transition from wool to cotton was a factor in Rochdale's reputation for radicalism and its espousal of Chartism; most of the original members of the Rochdale Friendly Co-operative Society, founded on Toad Lane in 1832, were hand-loom flannel weavers who saw their trade in decline. Their society failed and the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society, founded in 1844, again on Toad Lane, had an altogether broader membership. This radicalism was often filled with contradictions: Rochdale's most famous son, John Bright (1811-89), the great Parliamentary orator, promoter of free trade, opponent of the Crimean War and co-founder of the Anti-Corn Law League, was a partner in the cotton spinners John Bright & Brothers, who brought Irish immigrants over to staff their mills, housing them in mean back-to-backs in the north of the town, and opposing any union activity; this Mount Pleasant area quickly became one of the town's most notorious slums.

This map captures Rochdale before most of the large out-of-town mills were built. A sign of things to come was the Arkwright Mill (top of map), built 1885 by the Arkwright Cotton Spinning Co. The industry peaked in the years before the 1st World War and in 1929 there was an attempt to strengthen it through consolidation, the Arkwright mill being one of the 104 that was taken over by the Lancashire Cotton Corporation. It became part of the Courtaulds group in 1964. In 1891 this mill was unusual in having both mule and ring spindles and was the largest of the mills shown here. However, many of Rochdale's mills would be elsewhere in the parish; Bright's Fieldhouse Mills, for instance, were north of the map.

Richard Townley, of Belfield Hall, like Alexander Butterworth before him, was a High Sheriff of Lancashire, and was probably one of the Rochdale businessmen who put forward the idea of a Rochdale Canal in the 1770s. In 1776 they commissioned James Brindley to survey a possible route. A new survey was made by John Rennie in 1791, with proposals for branches to Rochdale and Oldham; there were the usual objections from millowners, who feared for their water supply, but on 4th April 1794 an Act was passed, authorising construction; the decision was then made that the canal should be a 'broad' one, allowing vessels 14 ft wide, a distinct advantage over the Huddersfield Narrow Canal. The Rochdale Branch Canal was first to be opened, in 1798, and attracted industry, noticeably here the Union Sawmills and the Vicars Moss mill.

The main canal was fully opened between Manchester and Sowerby Bridge - where it met with the Calder & Hebble Navigation, so forming a trans-Pennine route - in 1804. By 1839 it was carrying 875,000 tons a year, and though traffic was affected by the opening of the railways it rallied to see a peak loading of 979,000 tons in 1845. In 1855 the Rochdale Canal was leased by a consortium of four railway companies, led by the Lancashire & Yorkshire, and this agreement lasted until 1890. The canal remained profitable into the 20th century but traffic fell off during the 1st World War and in 1923 the reservoirs were sold to various local authorities for drinking water. The last through journey took place in 1937 and most of the canal was formally closed in 1952. A preservation society was formed and the main canal was fully reopened in 2002. We might note the Grade II listed Belfield Bridge across the canal, leading to Belfield Mill (see NE marginalia) and noted as an early example of a skew bridge. However, the half-mile Rochdale Branch Canal was filled in during the 1960s and the canal wharf and basins, part of which had been filled in by the 1930s, are now covered by retail units and car parks.

The main canal was fully opened between Manchester and Sowerby Bridge - where it met with the Calder & Hebble Navigation, so forming a trans-Pennine route - in 1804. By 1839 it was carrying 875,000 tons a year, and though traffic was affected by the opening of the railways it rallied to see a peak loading of 979,000 tons in 1845. In 1855 the Rochdale Canal was leased by a consortium of four railway companies, led by the Lancashire & Yorkshire, and this agreement lasted until 1890. The canal remained profitable into the 20th century but traffic fell off during the 1st World War and in 1923 the reservoirs were sold to various local authorities for drinking water. The last through journey took place in 1937 and most of the canal was formally closed in 1952. A preservation society was formed and the main canal was fully reopened in 2002. We might note the Grade II listed Belfield Bridge across the canal, leading to Belfield Mill (see NE marginalia) and noted as an early example of a skew bridge. However, the half-mile Rochdale Branch Canal was filled in during the 1960s and the canal wharf and basins, part of which had been filled in by the 1930s, are now covered by retail units and car parks.

The Manchester & Leeds Railway closely followed the route of the canal, but here was diverted nearer to Rochdale, though still half a mile from the centre. It was opened between Manchester and Littleborough on 3rd July 1839 and in 1841 the line was fully open through Hebden Bridge to Normanton, whence trains continued to Leeds on the North Midland Railway. Despite the unpromising terrain, the line was notable for its modest gradients, a tribute to its engineer, George Stephenson. In 1847 the railway was incorporated into the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, becoming that company\rquote s principal trans-Pennine route. The first Rochdale station was opened on the east side of Oldham Road but was criticised for its poor facilities; in 1889 it was rebuilt about 300 yards to the west, almost off the map.

Rochdale was a modestly busy junction, with connecting lines to Bury (opened 1848 but off this map to the SW), Oldham (1863) and Bacup (1881). The Oldham line has now been converted for use by Metrolink trams, crossing the main line by a flyover and then continuing along Richard Street and Drake Street into the town centre. Of greatest interest to us here is the Facit Branch, somewhat reluctantly built by the L&YR, against their better judgement and largely through a need to see off potential opposition from the Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway. Initial plans were for a branch to Facit, on which work started in 1862, but even this was not opened until 1870. Work included a major viaduct across the Roch and, several miles later, the Healey Dell viaduct across the River Spodden. In 1878 work started on the extension to Bacup and this duly opened, with the minimum of ceremony, in December 1881. Within three years trams between Rochdale and Whitworth were taking away some of the trade. Freight traffic, especially stone from quarries at the Rossendale end, was always more important than passenger, and a 1914 timetable shows just 12 trains a day in each direction (14 on Saturdays), stopping at all stations; Wardleworth station, however, was quite well placed for the town centre and a few Manchester-Rochdale trains terminated here. Passenger services ended long before Beeching, on 16th June 1947, but the line remained open for freight into the 1960s, with complete closure in 1967. The viaduct across the Roch was demolished in 1972.

The Facit Branch quickly lost some of its traffic to the trams. The Manchster, Bury, Rochdale & Oldham Steam Tramways Co was formed in 1881, with ambitions to run trams in all its constituent towns, and would ultimately operate the country's largest network of steam tramways - over 30 miles - although the enforced adoption of different gauges prevented much through running. The Rochdale lines were at 3ft 6in gauge, whereas those in Bury and Oldham were standard gauge. Construction in Rochdale began in July 1882 and the lines to Littleborough and along Oldham Road to Buersil were opened on 7th May 1883. "A large crowd collected to watch the starting of the cars, one being despatched from the Wellington Inn to Buersil and the other to Littleborough. Considerable difficulty was for a time experienced in getting up the Drake Street incline near the Wellington".

Other lines quickly followed: along Whitworth Road to Healey on 1st November 1883 and extended on to Facit in 1885, in direct rivalry to the Bacup line; via Sudden and Heywood to Hopwood and Heap Bridge on 30th May 1884; and an extension of the Buersil line to Royton in 1885. A tram deppt was opened on Entwistle Road, housing most of the network's 62 narrow-gauge steam locomotives and 55 trailer cars; others (along with standard gauge vehicles for the Oldham lines) were housed at Royton depot. As shown here the Entwistle Road sheds were (from W to E) for maintenance, locomotives and trailers. Other lines were authorised but never built, westward from Cheetham Street, and along Milnrow Road. The steam trams, dirty and unpopular, would be short-lived. The company was in financial difficulties by the late 1880s, dropped 'Manchester' from its title, and by 1891 had abandoned the Healey-Facit and Heywood-Hopwood sections. By then thoughts were turning to other traction to replace the 'malodorous' steam trams, and the Bury Road route was opened to electric trams in 1902. Others followed and the last steam trams would run on the Littleborough route in 1905. Electric trams ceased in 1932 - a short stretch of track survives near St James's church - but are being revived by Metrolink.

Victorian civic pride was often reflected in municipal buildings, towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire especially vying with each other for distinction, and nowhere is this more apparent than in Rochdale, which boasts one of the country's great town halls. As usual, discussion about a building began almost the moment borough status was acquired in 1856, and in 1864 an architectural competition was held. This was won by William Henry Crossland (1835-1908), and the foundation stone was laid by John Bright in 1866. A local newspaper reported that "We shall indeed have something more to boast of than Tim Bobbin's grave". Crossland was a pupil of G G Scott, would later be celebrated for two other masterpieces, the Holloway Sanatorium and Royal Holloway College in Surrey, but also designed many fine buildings around his native Yorkshire. His life has always been something of an enigma; he disappeared from public life in the 1890s and died almost penniless, perhaps as an alcoholic. The building of the town hall was marred by disputes, especially between the masonry firm, Warburton Bros of Harpurhey, and the clerk of works, James Kitchen, who noted that "The tower walls above the floor is built of rubble stone that I would not build a common cottage of" and "If that portion of the tower wall is not taken down and rebuilt with materials as per specification and one through stone in every superficial yard of walling I cannot be responsible for the tower standing. The bricks for the inside wall is of a very bad quality and the joints not flushed up, the bricklayer says he has got his orders from Mr Warburton that he must not do the work to my orders. The mortar has got too much sand in it". Clearly these disputes rumbled on for Kitchen was replaced in 1868 by J Brady, who would remain clerk of works until completion in 1871, though by that time the cost had increased from an original budget of £20,000 to nearer £160,000. Some of this increase was attributed to the mayor, George Leach Ashworth, who supervised the work and made 'recommendations'. The town hall is most famous for its exterior, but the interior is even more impressive, with fine tiling, stained glass and stonework. A grand staircase leads up the Great Hall, where a vast but somewhat heavy painting of Magna Carta by Henry Holiday is overshadowed by the stencilled wall decor, a hammerbeam roof, and stained glass windows delighting in the kings and queens of England. This last feature is said to have appealed especially to Adolf Hitler, who spoke of transporting the windows to a triumphant Germany.

The town hall was surmounted by a 240ft clock tower and wooden spire but by 1882 this was being damaged by dry rot. In March 1883 Crossland agreed to supervise restoration of this but the following month the spire was destroyed by fire, possibly accidentally ignited by workmen preparing it for demolition. The fire crew based at the rear of the building were criticised for their slowness in reaching the blaze. Perhaps Crossland was too busy by this time, or perhaps there were concerns about the previous cost overrun; in any case, the commission for a new clock tower was given to Alfred Waterhouse, and this was completed in 1887.

The town hall was surmounted by a 240ft clock tower and wooden spire but by 1882 this was being damaged by dry rot. In March 1883 Crossland agreed to supervise restoration of this but the following month the spire was destroyed by fire, possibly accidentally ignited by workmen preparing it for demolition. The fire crew based at the rear of the building were criticised for their slowness in reaching the blaze. Perhaps Crossland was too busy by this time, or perhaps there were concerns about the previous cost overrun; in any case, the commission for a new clock tower was given to Alfred Waterhouse, and this was completed in 1887.

The Town Hall remains the highlight of Rochdale, and it remains unfortunate that more has not been made of Crossland's plans for a grand piazza opposite. It is a shame that the new trams do not turn left at the bottom of Drake Street to terminate here, and help create a centre worthy of this proud old Lancashire town.

©Alan Godfrey, February 2014

Principal sources: Clare Hartwell et al, The Buildings of England: Manchester & the South-East (Yale, 2004); Edward Law, William Henry Crossland, Architect(web pages, 2001); Vicky Nash et al, Newbold Hall, Rochdale: An Archaeological Excavation (www.cfaa.co.uk, 2010); Gordon Suggitt, Lost Railways of Lancashire (Countryside Books, 2003); Victoria County History of Lancashire, Vol 5 (Constable, 1911); G.T.Whitworth, Bobbins: A short History of the Textile Industry in Rochdale (Littleborough, 2009); Tony Young, Tramways in Rochdale (LRTA, 2008).